As predicted, the Labour Party, with Kier Starmer at the helm, has managed to win 412 out of 650 seats in Parliament, which gives them a substantial majority despite no real gains in voter share. However, the Conservative Party saw their previous majority drop to 121 from 371 seats. The questions this election has highlighted are fascinating, from the resurgent Liberal Democrats and a breakthrough by Reform UK, which have once again highlighted the UK’s strange commitment to what is called the first past the post system.

So, what is the FPTP system? In the UK, the country is divided into 650 constituencies, each represented by an MP. Voters are then given a single vote on their preferred candidate. The candidate with the most votes wins. However, this does not mean they have the majority of support; they simply have to beat the other candidates.

The party that wins 326 seats or more can then form a majority Government. This sounds simple, but with the collapse of the conservative vote, FPTP no longer works. For it to remain the optimal process, you need to maintain a de facto two-party race. The system’s simplicity in a two-party framework is why FPTP has been popular for so long in the UK.

The political landscape of Britain in 2024, however, is not a simple two-party race anymore, and the fact that FPTP does not reflect this highlights why it is no longer fit for purpose. This election has shown how disproportionate representation is in the UK and how millions of votes are wasted—yes, millions.

The best way to show this would be to compare voter choices with proportional representation, a far more appropriate system to reflect a multi-party landscape no longer dominated by two parties.

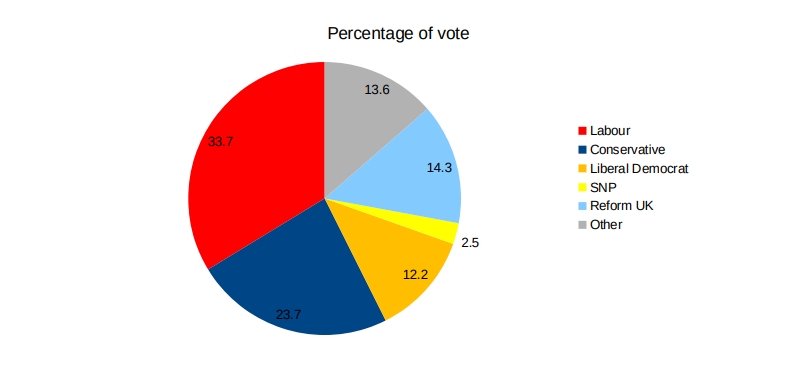

Chart 1

Chart 1 shows each party’s overall percentage of votes in the general election. Using this data, we can determine what Parliament would look like using a PR system, keeping the original 650 seats.

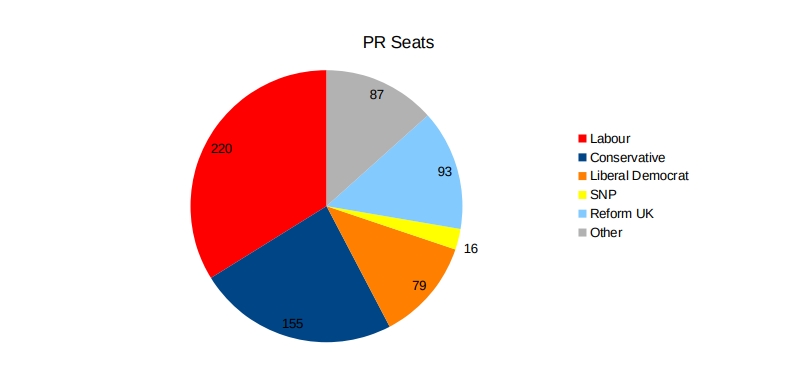

Chart 2

Chart 2 reflects the number of seats each party would have won if the UK had used PR. This also shows how FPTP favours the two-party system. This will become even clearer when we look at the share of seats taken by parties in Parliament now.

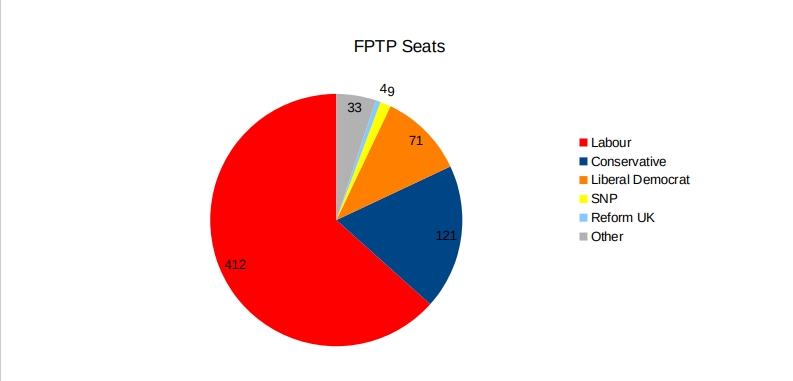

Chart 3

Chart 3 shows us just how disproportionate FPTP has become compared with better alternatives in what is now a multi-party country. It is no longer acceptable for voters to be punished for voting sincerely for change. Why should millions of votes be ignored because they chose not to vote for the two main parties?

Yes, Labour won this election, but who lost? Britain, or the 66.3% of the electorate who didn’t vote for Labour, are the losers. How long can a representative government continue with such disproportionate representation? Take the 4 million voters who ticked Reform UK; a mere 4 seats will represent them, whereas 5 seats will represent the 170,000 Democratic Unionist Party voters. On the left, the 2 million Green Party voters are represented by 4 seats, while 9 represent the 700,000 SNP voters. That’s not even mentioning the disproportionate representation enjoyed by the Liberal Democrats.

So, the question is, how long can the UK continue using an electoral system that does not proportionately represent Britain in 2024? I have no illusions that Labour will dismantle the system that has given them such a huge majority; however, if people believe Labour can govern the country better, you have not been paying attention.

FPTP will make way for a more proportionate system, but only after the electorate realises that Labour is just as useless as the Conservatives. One positive, however, from this election is that one of the two pillars holding this rotten system up has now fallen. We only have to keep pushing, and the second pillar will go the same way.