Immigration referendum explained

Why is it needed?

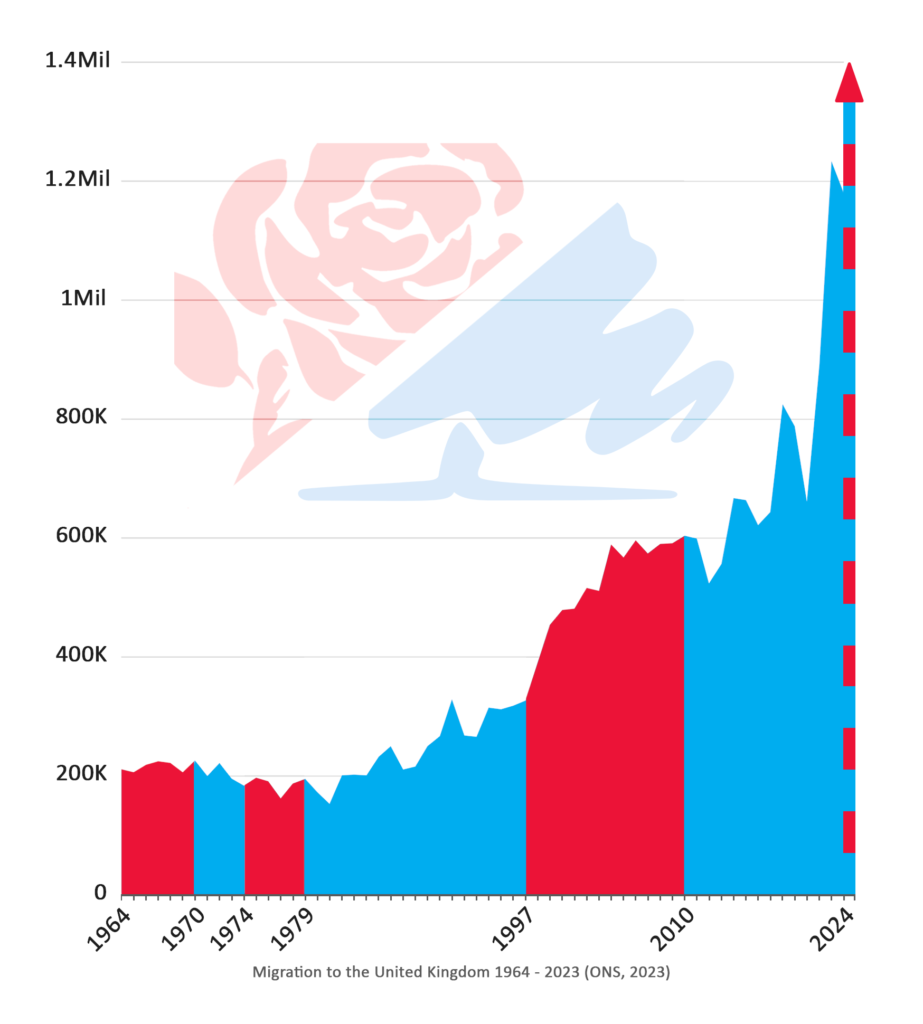

Immigration rates have reached unprecedented levels, yet the will of the people remains disregarded. We have not been consulted on this, and public opinion polls and election results have consistently demonstrated strong opposition to large-scale immigration. Nevertheless, political leaders have implemented policies that have dramatically altered the country without our consent, particularly since 1948 and more markedly from 1997 onwards.

Tony Blair’s New Labour Government initiated mass immigration with the intent to ‘rub the right’s nose in it’ and reshape the nation’s identity. Blair and his associates aimed to transform the country from a proud nation-state with a deep historical connection to its people into one defined by “multiculturalism”—a political concept that has led to significant inter-ethnic tensions and considerable hardship for our communities.

Despite their pledges, subsequent Tory governments did little to address the issues initiated by Blair’s policies and, in fact, exacerbated them. Immigration figures surged from 300,000 annually to 1.4 million under their watch. They failed to address the presence of pro-immigration and far-left activists within the civil service, even in the face of whistleblowers’ revelations. Furthermore, they oversaw a Home Office with quotas for increasing the hiring of ethnic minorities. Publicly, they adopted the corrupt language of “British values,” which, in reality, amounted to liberal rhetoric suggesting that anyone is welcome as long as they promise to align with liberal viewpoints.

New parties such as Reform UK are similarly dominated by liberal ideologies. They continue to uphold the same “British values” rhetoric, advocating for quotas rather than implementing a moratorium on mass immigration, and marginalising or excluding individuals who discuss demographic changes. It is unlikely that they will evolve into the force the country truly needs, and even less likely that they will be in power five years from now.

It is evident that immigration policy and law are unlikely to change through general elections in the near future, especially given the limitations of the First Past the Post (FPTP) system. Politicians and commentators who voice concerns about immigration have thus far been ineffective in creating meaningful change. This situation prompts the question of why they do not collectively support Proportional Representation (PR) and rally behind a radical party advocating for PR, such as ours, as a viable solution for addressing these issues more effectively.

We have developed a political culture where we often criticise the actions of one faction and then simply vote for the opposing faction, rather than demanding that power be placed directly into our own hands. This approach perpetuates the status quo rather than addressing the root issues or exploring alternatives that could give citizens more direct influence.

A more direct form of democracy

In such a dire situation, it becomes necessary to take radical steps to overcome the disparity between elites and the electorate. Rather than begging politicians to make decisions that align with our preferences, we should appeal directly to the people, empowering them to make the choices themselves.

This concept is known as direct democracy, where citizens vote directly on solutions to serious national issues. It is not a fantasy; similar mechanisms have been successfully implemented in other countries—Switzerland, for example, regularly uses direct democracy in its governance.

What we propose is a mass movement for a binding referendum on immigration, putting the power to decide the future of immigration policy firmly in the hands of the people.

How would it work?

Parliament is sovereign and holds supreme legislative authority. To hold a referendum on any matter, an Act enabling that referendum must be passed. Historically, successful referendums on issues such as devolution or independence in Scotland have been largely advisory. In these cases, Parliament has taken the wishes of the people into account and acted on them subsequently, rather than being legally bound by the referendum result.

The concept of a ‘binding’ referendum can be confusing for some. Given Parliament’s supreme authority, it can set any conditions it deems appropriate. Our proposal is that rather than a referendum serving merely as an opinion poll with the electorate hoping that the government and Parliament will act on their wishes, the Act enabling the referendum should also include the new law. This new law would only take effect if the people vote in favour of it. This approach is not dissimilar to a “sunset clause,” where a law ceases to be valid unless Parliament chooses to renew it.

In essence, while Parliament must pass a law for it to become effective, in this case, Parliament would first pass an Act stating that the new law will become effective if the people approve it in the referendum.

What if the elites don’t listen?

If elites disregard the clearly expressed wishes of the people, it becomes increasingly difficult to maintain the claim of being a liberal democracy. Such a situation undermines the political structure and becomes politically untenable.

Historically, referendums in the UK have demonstrated that the will of the people is taken seriously and acted upon:

UK-Wide Referendums:

- 1975: European Communities membership referendum, should the United Kingdom remain a member of the Common Market? (Yes)

- 2011: Alternative Vote referendum, Should the UK adopt the “Alternative Vote system” for electing Members of Parliament, replacing the First Past the Post system? (No)

England:

- 1998: Greater London Authority referendum, which established a Greater London Authority, consisting of a Mayor of London and a London Assembly (Yes)

- 2004: North East England devolution referendum, on creating an elected regional assembly (No)

Northern Ireland:

- 1973: Northern Ireland border poll, on whether Northern Ireland should leave the United Kingdom and join the Republic of Ireland (No; the referendum was boycotted by Irish nationalists)

- 1998: Northern Ireland Good Friday Agreement referendum, on the Good Friday Agreement (Yes)

Scotland:

- 1979: Scottish devolution referendum, on whether there should be a Scottish Assembly (A small majority voted Yes, but it fell short of the 40% threshold required to enact devolution)

- 1997: Scottish devolution referendum, on two questions: whether there should be a Scottish Parliament (Yes) and whether the Parliament should have tax-varying powers (Yes)

- 2014: Scottish independence referendum, on the question “Should Scotland be an independent country?” (No)

Wales:

- 1979: Welsh devolution referendum, on whether there should be a Welsh Assembly (No)

- 1997: Welsh devolution referendum, on whether there should be a National Assembly for Wales (Yes)

- 2011: Welsh devolution referendum, on whether the National Assembly should have increased law-making powers (Yes)

A common critique of the 2016 European Union membership referendum (commonly known as Brexit) is that it did not yield the desired outcome, leading to considerable confusion during Theresa May’s Government over Article 50, the meaning of Brexit, should it be a “hard” or “soft” exit, and whether to hold another referendum. In addition to a lack of political will, several factors contributed to this situation:

- Lack of a Pre-Defined Implementation Plan: There was no pre-defined plan, nor was it written into law, detailing how Brexit would be executed.

- Complexity of the Debate: The debate involved multiple complex issues regarding the separation rather than focusing on a single, clear outcome.

- Negotiations with the EU: The need to negotiate terms with the European Union, which had its own agenda, further complicated the process.

In contrast, our proposal for a binding immigration referendum is different:

- It addresses a single issue for which a pre-defined plan can be written.

- It can be embedded into law beforehand to ensure it is binding.

- It does not require negotiations with a supranational entity.

What about the constitution?

Another critique is the constitutional position that one Parliament cannot bind future Parliaments; a law passed today can be overturned in the future. While this is true, it remains politically unfeasible for a democratically elected body to ignore the clear wishes of the people, expressed through referenda, and still claim to uphold democratic principles. Progressive liberalism may be disruptive, but it has its limits. What we have seen in countries such as Denmark is that once anti-immigration policy becomes so popular that it is enshrined in law, the parties that were originally opposed to it adopt the policy as if it were their own and maintain it when they are in power, as they would not be voted in otherwise.

The constitution of the United Kingdom is not codified into a single document; it is spread across various laws, precedents, and constitutional conventions. However, there is nothing preventing Parliament from modifying it to incorporate the concept of a binding referendum, if required. Furthermore, there is nothing stopping us from advocating for the constitution to be codified and only accepted or amended through binding referenda, as is the case in other countries.

But what if none of this works out?

Some may critique the movement by questioning what happens if it fails to achieve its goals or doesn’t even make it to Parliament for debate. Yet, even in that scenario, we would achieve something important: exposing the glaring divide between the will of the people and the entrenched interests of the elite. This alone could erode their support and awaken the public to more radical and necessary ideas of popular sovereignty—a principle that has driven transformative change since the Civil War. Moreover, by shining a spotlight on the adverse effects of mass immigration, we can further galvanise public understanding and urgency for action.

History shows that people power is far from a fantasy; it is a force to be reckoned with. When we unite and tirelessly pursue a shared political goal, we have the power to reshape the political landscape. In the early 1990s, who could have imagined that a referendum on leaving the EU would ever be possible, especially when most people had little understanding of the issue? Yet by 2016, not only was it possible—it had become essential to millions. The key to that success was a clear vision, unwavering determination, and a deep belief in the cause.

Today, opposition to mass immigration is already widely supported and the issues are plain for all to see; it is already more popular among the people than the desire to leave the EU was in 2016. If we apply the same focus and resolve, there is no limit to what we can achieve together. A binding immigration referendum could be within our grasp in just a few short years.

Questions & Answers

Where do you mean by binding?

In the context of referendums, “binding” means that the outcome of the referendum has a mandatory effect on the government or legislature. If a referendum is binding, it means that the decision made by the electorate must be implemented, as opposed to an advisory referendum where the government or Parliament can choose whether or not to act on the result. A binding referendum ensures that the will of the people, as expressed in the vote, is legally enforced.

What is popular sovereignty?

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a government is derived from the will and consent of the people. It signifies that ultimate power rests with the people, who can exercise this power directly or through elected representatives. In essence, it reflects the idea that the government’s legitimacy and authority come from the people’s approval and participation, whether through direct or representative mechanisms.

What is First Past the Post?

First Past the Post (FPTP) is an electoral system where the candidate who receives the most votes in a constituency wins the election, regardless of whether they achieve an absolute majority of the votes. This system is used in various elections, including general elections in the UK. In FPTP, the candidate with the highest number of votes in a given constituency becomes the Member of Parliament for that area. Sometimes that candidate gets elected with as little as 20 to 30% of the vote.

FPTP often leads to a mismatch between the total percentage of votes received nationally and the percentage of seats allocated.

What is Proportional Representation?

Proportional Representation (PR) is an electoral system designed to more accurately reflect the proportion of votes each party receives in the overall election results. Unlike First Past the Post, where the candidate with the most votes wins in each constituency, PR ensures that the percentage of seats held by each party in the legislature is proportional to the percentage of votes they received. This system aims to provide a more accurate representation of the electorate’s preferences.

What is a sunset clause?

A sunset clause is a provision in a law that sets an expiration date for that law unless it is renewed or extended by the legislature. This means that the law will automatically cease to be in effect after a specified period unless action is taken to renew it. The purpose of a sunset clause is to ensure that laws are regularly reviewed and updated as necessary.

We mention the sunset clause to highlight that laws can indeed be conditional upon external factors. Just as a law with a sunset clause can be invalidated if certain conditions are not met, it follows that a law could be validated if specific conditions are fulfilled. In the context of a binding referendum, this means that rather than merely serving as an advisory opinion, the act enabling the referendum could embed conditions that must be met for the new law to come into effect. This approach underscores the flexibility in legislative processes, allowing for laws to be enacted or nullified based on direct public input and specific conditions.

But how would the question be framed?

It is too early to provide a definitive answer, as the necessary public debate has not yet taken place. From our perspective, the first step would be to define mass immigration through this debate and clearly outline why it is harmful, so the public can fully understand the reasons for opposing it. Once this understanding of mass immigration is established, it would need to be codified, then the public can vote to stop it.

Our leaflet