This report sets out much of the case for remigration and, above all, dismantles the stock myths deployed by the liberal elites to sell mass immigration and to smear any argument for reversing demographic decline or returning the population to a sustainable level.

For clarity and brevity, we separate why from how. We set out the reasons, the evidence, the ethics and the national interest. Our comprehensive Remigration Policy, updated for 2025 and now in its final drafting stages, will set out how remigration can and should be implemented.

For remigration to succeed, it must be understood not only by specialists and politicians but by ordinary people. The old slogans, such as “diversity built Britain” or “we’ve always been a nation of immigrants”, are not harmless clichés; they are falsehoods used to stifle our people and to manufacture consent for a project that harms us.

We show that state bodies, politicians, journalists and NGOs have misled the public, and that the policies they condemn would, in fact, benefit our country. Remigration would allow our people to live in peace, restore social cohesion, ease pressure on housing and services, and put us back on a path to real prosperity.

Our economists demonstrate that mass immigration is a net fiscal drain, while a well-run remigration programme would not only cost little but also deliver long-term savings in the hundreds of billions, relieving structural pressures.

It is not too late. Nations are saved by will and truth. Understanding and making use of the facts set out here is the first step to saving ours.

The sections that follow address each mainstream claim in turn, explain why it is wrong, and set out the national interest in remigration. Press one of the buttons from the menu below to jump to a section:

MYTH 1: “We’ve always been a nation of immigrants”

The assertion that “We’ve always been a nation of immigrants” is a barefaced lie.

a) Our ancient roots (pre-1066)

- 75 % of our people’s ancestry precedes even the first farmers of the British Isles1.

- The People of the British Isles Project2 identified 17 distinct genetic clusters that have persisted unchanged since about AD 600.

- While the Romans left no significant genetic legacy, the Anglo-Saxon and later Viking incursions each account for around 10% of our DNA3.

- The Normans added around 1% despite replacing the native aristocracy.

- Our peoples’ heritage is derived entirely from the peoples of North-Western Europe, of which the British Isles are a part.

This evidence shows that our ethnogenesis has endured for at least 1,400 years. In England especially, the population united by King Athelstan in 927 AD was essentially the same as that found a millennium later4.

b) Stability between 1066 and 1945

The only noteworthy migration between the Norman Conquest and the Second World War was that of the Huguenots. Approximately 50,000 French Protestants arrived across four decades, adding roughly 1.25 % to the population by 16005. Although they shared our religion and a broadly similar culture, they still waited more than a century for naturalisation in 17086.

From Elizabethan England (1558–1603) to the official counts of 1770 and the 1911 census, the Black population never exceeded 10,000 individuals7, with most working as dockside labourers or in domestic service8.

No significant Black population existed until 19609 and no significant Asian population existed until 1980 in Britain.

c) Post-1945 disruption

On the eve of the Second World War, there were only 7,000–10,000 non-Western residents in the UK, or 0.015 % of the population. Even by the 1951 census the figure stood at just 40,000, or 0.08 %.10

The first sizeable non-Western arrival was a private Caribbean passage in 1947-48. The passengers were neither invited by the government11 nor required by the economy. They answered a misleading advertisement designed to fill what would otherwise have been an empty return voyage of the Empire Windrush. The celebrated “Windrush Generation” is a modern myth, born of a shipping company’s profiteering and the need to justify multiculturalism.

Britain was not short of labour in 1947-48: unemployment averaged 2.5–3 % between 1946 and 1952, peaking at 12 % in February 1947 while demobilised servicemen were still seeking work12.

Until 1960, the UK remained 99% “White British” and “White Irish”, having rebuilt successfully after the war. Then, largely through ministerial ignorance and liberal ideology, the borders were opened to annual inflows in the following waves13:

- West Indian migration (1947-62)

- Indian migration (1960-70)

- Ugandan Asians following Idi Amin’s expulsion order (1972)

- Pakistani migration (1965-75)

- Bangladeshi migration (1980-90)

Every wave since 1947 has brought social frictions, ethnic clustering and white flight. The post-1945 pattern is therefore one of unnecessary and harmful mass immigration, not an organic continuation of our past.

1 Oppenheimer, S., The Origins of the British, (2003): “75% of British Ancestry arrived long before the first farmers. This applies to 88% of the Irish, 81% of the Welsh, 79% of the Cornish, 70% of the Scots and 68% of the English… The English are only 5.5 to 15% Anglo-Saxon, and about the same is Viking”. See also: Sykes, B., Blood of the Isles (2006).

2 The People of the British Isles Project, Oxford University, 2015

3 Oppenheimer, S., The Origins of the British, (2003)

4 West, E., The Diversity Illusion, (2013): “The English of 1927 were more than 90% the descendants of the English of 927” is the exact quote.

5 Brain, J., The Huguenots – England’s First Refugees, (Historic UK). These are for the most part widely known and uncontested historical facts.

6 As above.

7 Winder, R., Bloody Foreigners: The Story of Immigration to Britain, Ch.8 (2010)

8 As above.

9 The Commission for Racial Equality estimated a ~400,000 “non-white population” in the UK in 1961.Haug et al.’s estimate of ethnic minorities in 1961 (of ~550,000) appears to be an overestimate. The census did not collect ethnicity data in 1961.

10 Spencer, I., British Immigration Policy since 1939, 1997; also Whitfield, J., The Metropolitan Police and Black Londoners in Post-War Britain, 2004; also Haug et al., The Demographic Characteristics of Immigrant Populations, 2002; also Census Data via NOMIS.

11 House of Commons 16th June 1948, see also: Migration Observatory, UK Public Opinion toward Immigration: Overall Attitudes and Level of Concern, 2025 (“In British Election Studies for 1964, 1966 and 1979, 85+% have consistently said that too many immigrants were let in”)

12 Denman, J., & McDonald, P., Unemployment Statistics from 1881 to the Present Day, (1996)

13 Haug et al., The Demographic Characteristics of Immigrant Populations, (2002)

MYTH 2: “Diversity built Britain”

The claim that “Diversity built Britain” is quite frankly laughable. This is a slogan designed to manufacture a false past and deny our people their rightful credit. Until 1971, the UK Census recorded no meaningful non-indigenous population. Modern Britain was therefore built by our own people.

a) Industrial achievement

The Industrial Revolution began in Britain around 1760, driven by our engineers, entrepreneurs and inventors. Britain developed and exported an estimated 40% of the world’s most important inventions (including steam power, railways, and modern medicine) building on already advanced architecture, canals, roads, bridges, universities, legal systems and forms of government.

In the nineteenth century, Irish workers were particularly significant on canals and railways, making up between 10% and 30% of the workforce on these projects1. The rest were English, Welsh and Scots, and Ireland was part of the same kingdom at the time. This was not “diversity” in the modern liberal sense, but cooperation among neighbours.

b) Post-war reality

Reliable labour-force data for construction, mining and similar sectors are sparse. The evidence that does exist, however, contradicts the “diversity built Britain” narrative:

- The NHS was established in 1948, with a migrant workforce of zero. By 1965, an estimated 4,000 nurses were from the Caribbean, just 1.6% of the total nursing work-force2.

- Immigrants otherwise entered the less-skilled professions, such as in the postal service or in the public transit systems of London. There is no evidence of significant immigrant representation in the construction sector or in the establishment of public services.

None of these contributions resembles the wholesale rebuilding of Britain’s housing stock or critical infrastructure between 1945 and 1960. Every modern institution (including the NHS) was conceived of, financed and built by us. Even in 1991, the UK population remained 92.5% “White British” according to the Office for National Statistics3.

The notion that “diversity” built our country is a historical falsehood intended to sap pride in our own achievements by handing them to others. The slogan implies that London was about to “choke on its own homogeneity” until saved by these largely unskilled newcomers. The facts say otherwise. Britain was built by our people. The record is clear.

1 Sullivan, D., Navvyman, (1983). See also Brooke, D., The Railway Navvy: ‘That Despicable Race of Men’ (1983).

2 We are using the midpoint of 3,000-5,000 from Snow, S., & Jones, E., Immigration and the National Health Service: Putting History at the Forefront and a denominator of 240,000 as justified by an estimate from Hansard.

3 Census Data via NOMIS; See also: Jivraj, S., How has ethnic diversity grown 1991-2001-2011?, (2012)

MYTH 3: “Illegal immigration is the problem”

Illegal entries grab the headlines, but represent a fraction of what is really happening. In 2024, there were 42,809 illegal entrants, which are barely 4.5% of the 948,000 people who arrived in total. By focusing on that 4.5%, politicians dodge questions about the far larger, far costlier inflows of legal migration.

a) Illegal immigration

- 86% of detected illegal entries arrive by small boat1. Accommodating these migrants alone costs £1.5 – £2.2 billion per year2 3.

- Add schooling, healthcare, allowances and new bureaucracy and that tally rises to £3.5 – £4.7 billion per year4 5.

- Labour’s policy of dispersing claimants nationwide (instead of detaining them centrally) has produced crime spikes wherever hotels and hostels are sited, followed by protests from worried residents.

b) The larger, hidden cost of legal immigration

- “Grooming Gang” perpetrators are mainly men of Pakistani, Bangladeshi and certain other minority backgrounds, all here legally and often for decades.

- The most recent terror attacks on the public have been planned by legally settled migrants; the security services report that about 75 % of MI5’s caseload is Islamic extremism originating inside the country6.

- It is important to remember that legal migration is sometimes downstream from illegal migration: asylum-seekers destroy their passports to foil deportation and then gain legal status; students without funds switch visa tracks or overstay.

- Even where this isn’t the case, average wage migrants often bring large numbers of dependants who do not work and who, per individual, cost the UK Government up to £617,000 over their lifetimes. when use of services is compared to taxation.

- The result is that wages stagnate, housing stocks tighten and living standards for our people fall all while illegal entry is paraded as the only “problem”.

Illegal migration is costly and highly visible, but it is only the tip of a much larger iceberg. The far greater burden comes from legal routes that flood the country with people that we cannot afford to house, the economy does not need, and commit the most heinous crimes against our people. The government and the media keep the spotlight on “small boats” to hide the scale of the real issue.

1 Home Office, How many people come to the UK irregularly? (2025). See also Migration Watch, Channel Crossings Tracker, (ongoing).

2 National Audit Office, The Home Office’s Asylum Accommodation Contracts, (2025).

3 Ehsan, R., Fixing the UK’s Broken Asylum System, Policy Exchange, (2023)

4 As above.

5 Cole, H., and Godfrey, T., UK’s Outrageous Migrant Hotel Bill Revealed…, (2025)

6 Braverman, S., Hansard, (2023); See also MI5, DG Ken McCallum gives Annual Threat Update, (2022)

MYTH 4: “Immigrants prop up the NHS”

The claim that immigrants prop up the NHS is merely another version of the broader myth that diversity built Britain.

a) Does the workforce reflect the wider population?

- For all of its existence the NHS has reflected the country it serves. In September 2011 the NHS employed 1,091,028 people.

- 84% of that workforce was recorded as “white”: virtually identical to the ONS figure of 86% for the wider population.

- By September 2021 the head-count had risen to 1,297,230, with 75.8 % recorded as “white”. The national figure is 81.7% for the wider population.1

Even accounting for that shift, personnel recorded as “white” remain over-represented in the critical frontline roles that keep the NHS functioning2:

- Ambulance crews: 96%

- Midwives: 86.7%

- Scientific, therapeutic and technical staff (STSS): 80%

- Infrastructure support: 82%

b) Why has the gap widened?

The gap has widened not because we are incapable of caring for ourselves, or because migrants possess a unique aptitude for healthcare, but because successive governments have preferred to recruit overseas instead of training and retaining our own young people.1

The slogan “they prop up the NHS” is a political alibi, not a demographic fact.

c) What has happened in recruitment and standards?

Since 2019, all medical roles have been exempt from the Resident Labour Market Test, which removes the requirement to offer jobs to domestic candidates first. This has opened the flood-gates to foreign recruitment, pushing aside our own graduates.

Unlike countries such as Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, the UK gives no priority to its own citizens for training or employment in healthcare.

The worsening pay, heavy workloads, and poor working conditions have driven many of the few doctors we do train to leave for better opportunities abroad.2 This brain drain only deepens our dependency on foreign workers, many of whom arrive from low-income countries with dubious standards of training.

As a result, between September 2022 and September 2023, Health and Care Worker visas surged by 135%, rising from 61,274 to 143,990.3

However, foreign-trained doctors now make up 37% of all licensed UK doctors but account for:

- 58% of fitness-to-practise concerns

- 60% of suspensions and erasures

and are twice as likely to be investigated, even after adjusting for location and speciality (GMC reports, 2019–2022)4.

The Nursing and Midwifery Council’s 2022–2023 report5 shows similar trends among overseas-trained nurses, particularly from India, Nigeria and the Philippines.

These groups are overrepresented in misconduct and sexual misconduct cases6 7.

This is not sustainable. Medical schools are currently turning away two qualified applicants for every one they accept. There is no shortage of ability in the UK, but there is a politically created bottleneck that favours foreign recruitment over national self-reliance.

1 Green, D., Capping University Places for Doctors is Insanity, The Telegraph, (2023).

2 Thomas, J Meirion., British-trained Medics Head to Australia in Droves, The Telegraph, ( 2025).

3 Home Office, Why Do People Come To The UK? To Work, GOV.UK (2023).

4 General Medical Council, Fitness To Practise – Annual Statistics Report, (2022).

5 Nursing and Midwifery Council, NMC Annual Fitness To Practise Report, (2023).

6 Adams, S., Foreign Trained Doctors More Likely To Be Struck Off, The Telegraph, (2011).

7 Professionals Standards Authority, Annual Report and Accounts 2022/23, (2023).

MYTH 5: “Migrants pay into our tax system”

We already have more people out of work than jobs to fill. While 1.5 million individuals are officially unemployed, over 9 million of working-age are economically inactive. With that level of spare capacity, importing additional low-skilled labour makes no sense.

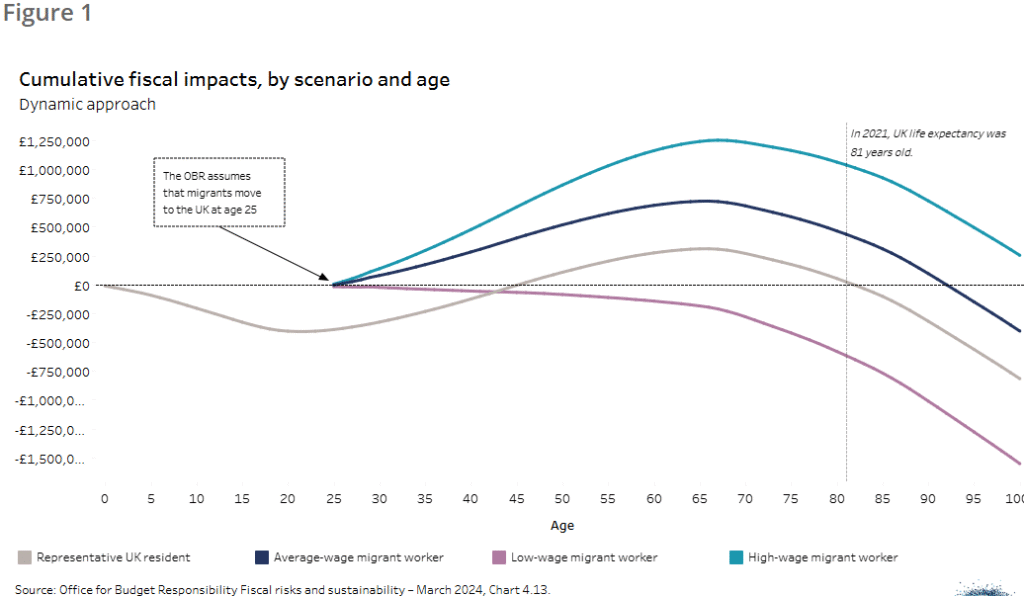

As Professor David Miles of the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) states, the fiscal (i.e., taxation and spending) effects of immigration “depend on how long migrants stay in the UK; whether they work; and how much they earn”1.

When two-thirds of recently-arrived immigrants will not even try to work, there is an additional burden placed on our public services and taxpayers. Mass immigration is therefore a fiscal black hole, not a lifeline.

a) Only a minority of migrants come here to work

- With a five-year average of 618,000 non-EU arrivals per year, only 31% arrive for jobs. The rest come for study, family reunion, asylum or other reasons2.

- Under the so-called “Boriswave”, 3.6 million visas were issued in 2021-24. Only 12% of those were “skilled worker” visas.

- Only 33% of those “skilled workers” earned a high wage3 while 54% earned a low wage. The Centre for Policy Studies estimates that 72% of “skilled workers” earn less than the UK average4.

- This means that only 4% of recent arrivals are guaranteed to be net contributors to the UK. The rest are likely to be net beneficiaries of UK taxation and spending.

b) What the non-working majority of migrants costs you

- The Centre for Policy Studies puts the lifetime bill for the so-called “Boriswave” (2021-24) at £234 billion, which is about £4 billion per year for decades5.

- The OBR concedes, after stacking their deck in favour of immigration, that low-wage migrants cost £617,000 per migrant over a lifetime6.

c) Why the OBR’s numbers are excessively optimistic

The OBR’s models for economic growth and for the net lifetime costs of migration are loaded with fairytale assumptions in favour of higher immigration. For example:

- All migrants magically arrive aged 25. This neatly dodges the cost of schooling or any other additional spending related to age.

- Every migrant walks straight into full-time work7 at the UK average wage, which is completely unrepresentative of the data that we do have.

- Every migrant is assumed not to work in the shadow economy; not to do cash-in-hand jobs; not to claim benefits for five years and not to send money abroad8.

If we swap those fantasies for real-world figures (low pay, dependants, welfare use), then the headline surplus turns into a huge deficit. The OBR has not been an honest referee; it is a cheerleader for open-borders ideology.

This is a graphical representation of their insanity:

1 Miles, D., Population Ponzi Scheme – Migration, Public Services and the Fiscal Outlook, (2025)

2 Office for National Statistics, Long Term International Migration (Provisional): YE December 2024 (2025)

3 The OBR defines a high wage migrant as earning being roughly 1.3 times the UK average salary, and a low wage migrant as earning roughly 0.5 times the UK average salary.

4 This is backed up not just by our proprietary analysis but also by the Telegraph, who note that 72% of migrants earn less than the average wage, meaning no more than 28% could be earning above it.

5 Bidwell, S., The Boriswave Indefinite-Leave-to-Remain Time Bomb is about to go off, (2025)

6 This outcome is replicated in the Netherlands, where the Dutch Central Planning Office found that representative immigrants arriving aged 25 and staying would impose a net lifetime cost of EUR 43,000, while an immigrant-descended child born in the Netherlands would have a net lifetime cost of ~ EUR 100,000.

7 Murray, A., Unemployment by Ethnic Background, House of Commons Library, link here.

8 Migration Observatory, Migrant Remittances to and from the UK (2025). The upper estimate for remittance outflows (£24.5 billion) represents an economic cost of 0.9% of GDP.

MYTH 6: “Remigration is too expensive”

Remigration is the systematic reversal of laws and policies that encourage mass immigration, while implementing new laws and policies to facilitate emigration instead.

While the establishment of Remigration Centres and flights will all cost money, this pales in comparison to the savings made by remigrating people who have always been a net cost.

We estimate that remigration will save us £24.2 billion per year. It is therefore not only economically desirable: it is necessary.

a) What does immigration enforcement currently cost?

Under the current immigration enforcement regime, the most expensive returns are enforced returns (such as deportations), especially when legal disputes are involved. In 2015, the Home Office estimated that the average cost of an enforced removal was £15,000 per person removed1, which translates to a cost of £20,750 in current prices.

In 2024, there were 8,164 enforced returns; 25,186 voluntary returns and 23,009 refusals at a port of entry. These figures imply that the government spends £170 million on enforced returns and up to £75 million on voluntary returns2.

The last available Home Office Annual Report budgeted a total of £537 million for immigration enforcement in 2024/253. This implies that, all costs considered, and at the current breakdown of enforced and voluntary returns, the cost of immigration enforcement is approximately £9,528 per person returned.

b) What are the costs of remigration measures?

The Homeland Party is committed to removing Foreign National Offenders currently in prison, out on parole, or previously convicted of serious offences. There are ~10,500 foreign nationals in UK prisons, and according to the CPS, there are an additional 12,000 living in the community who should be removed4. We estimate that this will cost ~£341 million5. Since the government already removes 5,034 foreign national offenders per year from UK prisons (cost: £105 million), this represents £236 million of additional government spending6.

The Homeland Party is also committed to the removal of all illegal migrants from the UK. In 2020, the Pew Research Centre estimated there were up to 1,200,000 people in the UK illegally7. There are, furthermore, 43,630 illegal migrants who arrive by small boat, undocumented air travel and lorries every year8. We anticipate that, as illegal migrants realise they will not be allowed to stay, the numbers arriving irregularly (particularly by small boat) will decrease.

As a result, we estimate that it will cost £11.43 billion (spread across multiple years) to remove the 1.2 million illegal migrants that are already here, and an additional £415.7 million per year to remove those arriving, which will decrease year-on-year9. These are the most expensive measures in the policy.

c) Can we afford not to implement remigration?

The vast majority of remigration measures either generate no additional spending or are in fact a cut to existing spending.

If we assume a two parliament timescale (8-10 years), then the initial stages of remigration would cost between £1.2 billion and £1.5 billion per year10.

However, in return, we would make gross savings (via lower government spending on welfare, policing, prisons, healthcare, etc.) of up to £25.56 billion per year11. So that’s a net saving of approx £24 billion per year.

The most expensive measures of a remigration policy are in fact savings, not costs. It is reasonable to expect that the more comprehensive policy, which we will publish soon, will likewise deliver savings. To describe remigration as “too expensive” is therefore a falsehood.

1 Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, An Inspection of Removals, (2014-15)

2 To estimate the cost of voluntary returns, we have assumed the upper limit of the £0 – 3000 of assistance available via the ‘voluntary return’ scheme (link) and multiplied by the number of voluntary returns completed. This is because even where recorded voluntary returns have received less than that, the Government covers the cost of flights, which is not included in the data.

3 Home Office, Annual Report and Accounts 2022/23, (2023)

4 Lord Jackson of Peterborough, Hansard, (2024)

5 At the current average cost of returns regardless of method (£9,528), it would cost £214.38 million to remove foreign national offenders. If all were enforced returns (£20,750), it would cost up to £466.87 million.

6 This is a midpoint estimate. The maximum additional government spend (assuming all enforced returns) would be £361 million.

7 Connor, P., and Passel, J., Europe’s Unauthorized Immigrant Population Peaks in 2016, Then Levels Off: New Estimates Find Half Live in Germany and the United Kingdom, (2019)

8 Home Office, Irregular migration to the UK, YE June 2024 (2024); See also Home Office, Irregular migration to the UK detailed datasets and summary tables, (ongoing).

9 These are midpoint estimates based on maintaining the current proportions of enforced and voluntary returns. The maximum possible estimate (assuming all enforced returns) would be £24.9 billion. The lowest possible cost (assuming all voluntary returns at maximum grant of £3,000) would be £3.6 billion.

10 This is based on midpoint estimates. The initial stages of remigration could cost as little as £366.75 million to £458.43 million per year (based on 100% voluntary returns) or as much as £2.53 billion to £3.17 billion per year (based on 100% enforced returns).

11 If there are officially ~15,539,900 non-British residents in the UK, and the initial stages of remigration target the 1,200,000 illegal immigrants plus 22,500 foreign national offenders in prison or on parole, then the proportion of government spending on immigration should decrease by 7.87%.

MYTH 7: “Migrants do not want to leave…”

But the data suggests otherwise. Contrary to the narrative that migrants come to the UK with no intention of ever leaving, many surveys show a significant number of first- and second-generation immigrants actively considering departure.

a) The desire to leave

A 2024 pre-election survey by audience engagement agency Word on the Curb found1:

- 66% of young first and second generation immigrants are considering leaving the UK, primarily for Europe or Asia.

- 59% report that quality of life in the UK has worsened, while 44% cite a desire to find better-paid work elsewhere.

Instead of ignoring these sentiments, those who wish to leave should be actively supported in doing so permanently. Voluntary emigration is a key part of remigration.

b) Other push factors

Further sources of disillusionment have been surveyed by the Black British Voices Project2.

- 87% of those surveyed believe businesses aren’t doing enough to address employment inequities, while 98% feel they need to compromise their identity in the workplace.

- 93% of those surveyed do not feel supported by the UK Government. As a result, 39% have expressed a desire to live elsewhere.

- This is despite extensive government and private industry spending on anti-racism and DEI initiatives.

This data points to a consistent and deeply felt frustration under multicultural dogma, and that for many, remigration would be positive step in their lives. Combine this with comprehensive remigration policy measures that encourage them to leave, and they will go.

1 Word on the Curb, Get(ting) Out, (2024)

2 Black British Voices, Black British Voices Project, (2023)

MYTH 8: “We need the population increase to pay for pensioners”

If only 4% of recent migrants are guaranteed to be lifetime net contributors (see myth 5 answer a), then most of the other 96% will never pay enough tax to cover their own pensions, let alone anyone else’s.

a) Why immigration cannot fund the State Pension

Migrants grow old too. Adding ever more people to “improve” the old-age dependency ratio is postponing the problem, not solving it. The international evidence is damning.

- In Denmark (2018), the net cost of immigration was 24 billion DKK per year. This was split into non-Western immigrants (who cost 31 billion DKK) and Western immigrants (who contributed 7 billion DKK)1.

- In the Netherlands (2021), the net cost of immigration from 1995-2019 was estimated to be a cumulative 400 billion EUR2.The same study then forecast that the cumulative net cost of immigration from 2020-2040 would be another 600 billion EUR.

- In Sweden (2017), the costs of immigration are expected to more than double the cost of the state pension system after tax3.

- In the UK (2014), two studies estimated the net cost of immigration from 1995-2011 at between £5.6 billion and £8.75 billion per year4.

Whether it is here or elsewhere in Europe, such economic losses make paying pensions harder, not easier. The UK’s state pension is “pay as you go”, meaning today’s taxes fund today’s retirees.

The majority of migrants we admit will, over the next 55-56 years, cost up to £617,000 each in services and pensions. They are a direct drain on the Treasury, not net contributors.

b) Why immigration does not improve the dependency ratio

Immigration is often touted as the way to improve the old-age dependency ratio (OADR). But the effect of immigration on birthrates and population aging is not what many economists think:

- While migrants often arrive with higher birthrates; those birthrates tend to converge to native levels within a generation.

- The effect of immigration is also that it depresses native birthrates: US studies imply that up to 22% of the decline in birthrates since 1971 is due to increased diversity5.

- While the highest-skilled and youngest migrants are most likely to remigrate for other economic opportunities; the lowest-skilled and oldest migrants are least likely to.

As a result, the supposed demographic benefits of immigration disappear, and do not improve the old-age dependency ratio over the long run. In fact, to just keep the dependency ratio stable (and therefore pensions as affordable as they are now), Professor David Miles of the OBR has predicted the UK would need explosive levels of immigration of at least 500,000 young people only every year for the next 40 years6.

Therefore, relying on immigration to pay for pensions is economic self-harm. It only works if each influx is followed by an even larger one: the very definition of a Ponzi scheme. If anything, our pension system needs to be backed by improved productivity, prudent savings, and a favourable tax and regulatory environment, not an endless queue at the border.

1 Finance Ministry of Denmark, Økonomisk Analyse: Indvandreres nettobidrag til de offentlige finanser i 2018, (2021). See also: The Economist, Why have Danes turned against immigration?, (2021) plus further analysis.

2 Ven de Beek, J., et al., Borderless Welfare State: The Consequences of Immigration for Public Finances, (2023).

3 Pensions Authority of Sweden (2017), as reported by Ohrn, L., Migrationen kan fördubbla statens kostnader för pensionärer, (2017).

4 For lower estimate, see Dustmann, C., and Frattini, T., The Fiscal Effects of Immigration to the UK, Discussion Paper Series CDP No. 22/13, UCL (2013); see also Dustmann, C., and Frattini, T., The Fiscal Effects of Immigration to the UK, The Economic Journal 124 (2014) F593-F643. For higher estimate, see Migration Watch (2014).

5 Solomon, D., E Pluribus Pauciores (Out of Many, Fewer): Diversity and Birthrates, (2024).

6 Miles, D., Population Ponzi Scheme – Migration, Public Services and the Fiscal Outlook, (2025).

MYTH 9: “Immigration benefits the economy, it increases GDP”

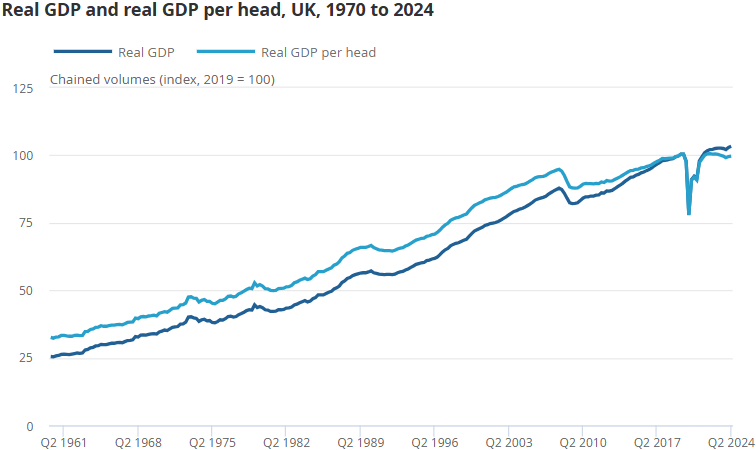

GDP, or Gross Domestic Product, is a measurement of how many goods and services an economy produces. It is not a useful measure of how well an economy is doing, not only because it does not account for trade-offs (such as inflation and pollution), but also because it also does not accurately measure living standards. This is why a majority of economists prefer to use real GDP per capita instead1.

Therefore, while previous estimates have found that immigration causes a slightly-less-than-proportional increase in GDP2, the true measure of economic wellbeing (real GDP per capita) shows that immigration reduces living standards. This is shown firstly by the fact that real GDP per capita grew by 2.75% per year during 1984-2004 and then only by 1.3% per year during 2004-2024.

More importantly, however, the recent surge of immigration means that real GDP per capita is lower now in 2024-25, than it was at the end of 2019.

This is because productivity growth has slowed as a result of immigration, which has in turn reduced the real wages of our workforce. Immigration reduces productivity firstly by labour substitution: firms hire cheaper foreign labourers instead of investing in the education and training of our workers. Immigration then further reduces productivity by factor substitution: firms hire cheaper foreign workers instead of investing in machinery and automation.

| Decade | UK Average Output per Worker Growth (%) | UK Average Output per Hour Growth (%) | UK Average GDP per Capita Growth (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970-80 | 2.05 | 1.93 | 2.05 |

| 1980-90 | 2.21 | 2.46 | 2.77 |

| 1990-00 | 2.06 | 2.37 | 2.21 |

| 2000-10 | 0.86 | 1.15 | 1.03 |

| 2010-20 | -0.18 | 0.67 | 1.12 |

Because of these two effects, labour productivity and real wages should be 12% higher than they currently are3. This is proven by the table4 (above) which shows that, as immigration into the UK increased from 1997 onwards, labour productivity collapsed.

Combined with taxation policies that discourage private investment and technology; an energy policy that commits to the most expensive sources; and a planning system5 that constrains growth and increases rents; productivity (and thus immigration) is a key reason that the UK is unable to establish an advantage in the production of high value added goods. This means it is harder for us to reindustrialise, expand our export markets, and to grow economically.

In addition to a worsened balance of payments position, immigration causes increased unemployment and economic inactivity, increased income inequality (via depressed wages and higher rents)6, and greater budget deficits (due to higher government spending). It is the latter most of all that is harming the UK: our budget deficit is currently £131 billion (or 4.8% of GDP). £107 billion of that is in interest7.

The estimated cost of immigration to the UK in current government spending is £324.8 billion per year. This is split out in Annexe A8.

1 Manning, A., The link between Growth and Immigration: Unpicking the Confusion, (2022).

2 Migration Watch UK, Contribution of Immigration to GDP, (2005) found that a just over 10% immigrant population was responsible for 9.8% of GDP. Borjas, G. J., Immigration and Economic Growth, (2019) also found a very weakly positive (gradient = 0.08) correlation between immigration and GDP.

3 Harari, D., Productivity: Economic Indicators, House of Commons Library (2025); see also What explains the UK’s productivity problem?, Productivity Institute (2024).

4 Bergeaud et al., Long Term Productivity Database, (2016) was the data source for this table. See also Office for National Statistics, Output per, (ongoing) for replication.

5 See Annexe B for further details.

6 Blau, F., and Mackie, J., The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine

7 Keep., M., The Budget Deficit: A Short Guide, (2025), House of Commons Library

8 See Annexe A for further details.

MYTH 10: “Employers won’t be able to hire native workers”

It is time to rethink the labour market model of the UK that prioritises foreign workers over domestic workers when wages increase.

a) Fiscal contribution of migrants

- Only 31% of immigrants on average arrive explicitly to work. The rest are dependants, students and asylum cases, many employed illegally in low-wage, low-skilled work.

- Only 4% of migrants are guaranteed to be net contributors to the UK Treasury over their lifetime. This indicates that the vast majority will be net recipients.

- There are 1.7 million working-age migrants who are either economically inactive; or unemployed; or dependent on welfare in the UK1.

- Excluding students, the taxpayer has spent £24 billion on economically inactive migrants between 2020 and 2023 inclusive.

This undermines any argument or suggestion that migrants are more productive, employable and hard working than our own workers.

b) Persistent labour shortages are a policy failure, not a population problem

For two decades (2004–24), the UK has averaged 700,000 net vacancies2. In May 2025 alone, there were 1.4 million active job adverts, mostly for low- to mid-skill roles3:

- Care workers

- Business development managers

- Payroll/bookkeeping clerks

- IT support technicians

- Cleaners

- Teaching assistants

- Catering staff

These roles would be filled by our own workers with an increase in real wages, or reforms to the tapering of work-related benefits that contribute to marginal tax rates of 55-71%4.

The UK has ~6 million working-age nationals who are economically inactive not because of a lack of willingness to work but because of policies that encourage employers to import cheap labour (via immigration) rather than raise wages.

The data suggest that the ongoing dependence on low-wage migrant labour masks the deeper structural failures of our overburdening tax system; the failure of education; a welfare system that traps people in poverty and inactivity, and a labour market that externalises the costs of training and social insurance on to the state, while relying on immigration as a disposable and cheap workforce. It is not the case that “British people won’t do the jobs.” It is that the incentive structure makes it irrational for them to do so, and profitable for businesses not to hire them.

1 Centre for Migration Control, The Cost of Migration: Economic Inactivity Amongst Migrants Aged 16-64, (2024).

2 Office for National Statistics, Vacancies and Jobs in the UK, (2025).

3 Office for National Statistics, Labour Demand Volumes by Standard Occupation Classification, (2025).

4 The marginal tax rate of 55% would apply to someone earning at or below the personal allowance (£12,570), while the rate of 71% would apply to those earning at or above £50,000 per year. See BBC News, “Why some parents effectively pay a 71% tax rate”, (2024).

MYTH 11: “It’s too late”

The vast majority of migrants in Western countries are still first or second generation; many retain dual nationality, foreign ties, and distinct cultural identities. In the UK:

- 80% of the foreign-born population arrived after 1991, meaning the demographic shift is relatively recent in historical terms.

- Roughly half of the UK’s non-Western population is foreign-born, implying a large number of dual nationals with strong legal and family connections abroad.

- People go back to their homeland all the time, and many of them want to (see Myth 7).

These are not abstract statistics. They are facts that show the window for policy correction is still open. Furthermore, large-scale demographic shifts can be reversed over multiple decades through comprehensive remigration policy, which involves systematically reversing laws, policies and incentives that facilitate mass immigration to encourage mass emigration instead.

Annexe A: Methodology and the Costing of Immigration

a) A note on methodology: defining the immigrant population

- For Census purposes, the Office for National Statistics does not use “immigrant” as an official category. The Census classifies people by country of birth, nationality, passports held, ethnic group and national identity1. In statistical usage, “immigrant” is usually taken to mean someone born outside the UK. The government does not routinely publish welfare statistics by immigration status, because most administrative systems do not record it.2

- One result is that, while non-UK nationals are eligible to receive a UK State Pension if they have sufficient National Insurance contributions, we cannot estimate how many recipients or the aggregate cost, because the Department for Work and Pensions has not published comprehensive statistics by nationality or immigration status.3

- Moreover, “immigrant” is not a comprehensive legal category. Since 1 January 1983, a child born in the UK is a British citizen only if, at the time of birth, at least one parent was a British citizen or was “settled” in the UK.4 An Irish citizen parent living in the UK is treated as settled.5 A person who is not a British citizen at birth may later be naturalised relatively easily once eligible, typically after a qualifying period of residence and settlement.6

- Therefore, for this exercise we will use the terms “indigenous” and “non-indigenous”. “indigenous” refers to people recorded with the “White British” and “White Irish” ethnicities, and “non-indigenous” refers to all other ethnic categories. This is an analytic definition for this report, not an ONS category. In our view, it provides the clearest picture not only of current immigration but also of past immigration and its downstream consequences7.

b) The Cost of Immigration: Welfare and Healthcare (£142.5 billion)

- The greatest proportion of government spending (~30%) is for social protection (i.e., benefits and pensions). There are theoretical barriers to immigrants receiving benefits within their first five years in the UK (“no recourse to public funds”); however, they are often ignored and said immigrants do have access to benefits after that period.

- The greatest single item of social protection spending is pensions, and according to the 2021 Census, 8.3% of people over-65 are non-indigenous. Most will be eligible for a form of state pension assuming minimum required contributions (10 years). On this basis, and using the Treasury’s Public Expenditure Statistical Analysis figures8, we estimate that the cost of immigration for pensions is £13.5 billion per year9.

- The next largest item of spending is sickness and disability, such as care and mobility components of Disability Living Allowance. This is an area where indigenous households do claim at a marginally higher rate than non- indigenous households. Therefore, our estimate of £21.4 billion as the cost of immigration is likely to be a slight overestimate.

- The next spending item is total family and children, which is likely to include things like child benefit, child tax credits and so on. Apart from Chinese households, the indigenous are least likely to claim child benefit (17%) and child tax credit (5%). By contrast, Black, Bangladeshi and Pakistani households are the most likely. Therefore, our estimate of £8.6billion is likely to be a significant underestimate.

- For housing-related benefit, again indigenous households are less likely to claim than Bangladeshi, Black and Pakistani households. Therefore, our estimate of £4.35billion is likely to be a significant underestimate. For the avoidance of doubt, this excludes the cost of asylum accommodation and related allowances for illegal immigrants, which costs £4.7 billion per year10, and comes out of the foreign aid budget.

- Next is unemployment. This is, ironically, something we have statistics for according to immigration status thanks to Freedom of Information Requests. In March 2025, £941 million per month was paid in Universal Credit to foreign nationals (who, if they have Indefinite Leave to Remain or refugee status, are eligible), which is a minimum of £11.3 billion per year11.

- Furthermore, it is difficult to keep methodologically consistent, as Public Expenditure Statistical Analysis (PESA) by HM Treasury classes a mere £1.3 billion as “total unemployment” spending.12

- Finally, for the ancillary social protection categories, such as “social exclusion n.e.c.” (not elsewhere classified and, for our purposes, including family benefits, income support, Universal Credit and tax credits rolled into one), £21.94 billion a year is likely an underestimate.

- Overall, immigration accounts for about £86 billion (22%) of social protection spending, between £80 and £91.6 billion on reasonable assumptions13.

- In terms of healthcare, the levels of demand placed on the NHS are roughly proportional to the ethnic breakdown of the population. The data implies that white patients demand fewer finished consultant episodes (76%) than their proportion of population (81.7%); however, this is not conclusive due to 14% of the data not having an ethnicity recorded.

- Immigration-related demand on the NHS costs about £56.6 billion, between £52 and £61.2 billion on reasonable assumptions.

c) The Cost of Immigration: Education (£42.4 billion)

- It is reasonable to believe that a greater than proportional percentage of the education budget is spent on immigration.

- The data indicate that 38.4% of primary school pupils; 37.8% of secondary school pupils; 32.0% of special school pupils and 25.4% of AP school pupils are from an ethnic minority background14 – and this is before we account for additional pupil premium funding; higher propensity to receive free school meals; the higher rate of Special Education Needs in some communities15 and costs of providing English as an Additional Language (EAL)16.

- As a result, we estimate the additional cost of education from immigration at £42.4 billion (or 35.7% of all education spending).

d) The Cost of Immigration: Policing and Prisons (£16.9 billion)

- Policing and Prisons are an area where accurate estimation is quite difficult. For example, in 2007, Robert Putnam found a robust positive correlation between ethnic homogeneity and social trust (the result of which being that increased ethnic diversity thus erodes social trust, causing individuals to “hunker down”, “withdraw from collective life” and “to distrust their neighbours regardless of the colour of their skin”). If communities with low social trust17 are understood to be more expensive to police, how can one estimate that? It is a detailed academic study in its own right and is certainly beyond this exercise.

- However, we can look at ethnic breakdowns of arrests by the police, prosecutions by the CPS and those imprisoned.

- The arrests data by ethnicity show that, at most, 411,405 out of 584,243 (or 70.4% of arrests) in 2022/23 were for the indigenous population18. The figures for stop and search show that, at most, 251,939 out of 421,189 (or 59.8%) were for the indigenous population.

- A reasonable estimate, therefore, is that 35% of the overall policing budget might be allocable to immigration, a calculation that arrives at £12.6 billion per year.

- If we account for prosecutions, the indigenous population is responsible for around 81% of prosecutions. This means immigration costs £2.11 billion here.

- And finally, there are the costs of prisons. Since prosecutions are roughly proportional to population, so too are custodial sentences. However, significant differences exist in both sentence length and violence rates19, which leads to a greater than proportional ethnic-minority prison population. Per the Lammy Review20, “there is no single explanation for the disproportionate representation of BAME groups” in the adult and youth prisons, but factors may include the severity of offence committed and the higher likelihood of ethnic minority defendants pleading not guilty in court.

- While the average sentence served for indigenous inmates increased from 15 months (2009) to 18 months (2017); the average sentence served by Asian and Black inmates increased from 19 to 27 months, and from 20 to 26 months respectively.

- As a result, in March 2024, there were 10,422 foreign nationals in UK prisons, and only 72% of the prison population was white (compared to 81.7% of wider population)21.

- We therefore estimate that immigration is responsible for between £2 billion and £2.4 billion per year with respect to costs of incarceration.

e) The Cost of Immigration: Other (£123 billion)

If we take a proportion to population approach for government spending where it is not immediately obvious that adjustments are required, then we can estimate that the cost of immigration is:

- £33.0 billion of accounting adjustments

- £22.1 billion for debt interest22

- £16.3 billion for non-foreign aid and non-debt general public services

- £16.3 billion for defence;

- £11.8 billion for transport;

- £8.7 billion for non-transport and non-primary industry economic affairs;

- £5.7 billion for non-benefit spending on housing

- £4.4 billion for environmental protection

- £3.7 billion for culture and religion

- £1 billion on Fire Protection Services

1 ONS, Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion: Census 2021 and Question development for Census 2021.

2 Department for Work and Pensions, series overview and latest releases: Nationality at point of National Insurance number registration of DWP working age benefit recipients. See also the 2013 bulletin referencing the original 2012 ad-hoc release.

3 Department for Work and Pensions, series overview and latest releases: Nationality at point of National Insurance number registration of DWP working age benefit recipients. See also the 2013 bulletin referencing the original 2012 ad-hoc release.

4 British Nationality Act 1981. Gov.uk, Apply for citizenship if you were born in the UK.

5 House of Commons Library explainer.

6GOV.UK, Apply for citizenship if you have indefinite leave to remain.

7 ONS, Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion: Census 2021 and Question development for Census 2021 .

8 HM Treasury, Public Expenditure Statistical Analysis, (ongoing)

9 There will be margins of error either side of this estimate. For example, ethnic minority pensioners are poorer and therefore claim pension credit at higher rates. There may be some however who do not claim entitlements such as pension credit, winter fuel allowance, and so on, if they feel they do not need it.

10 Cole, H., and Godfrey, T., UK’s Outrageous Migrant Hotel Bill revealed…, The Sun (2025)

11 Hymas, C., Foreigners Claim £1bn per month in benefits, The Telegraph (2025)

12 HM Treasury, Public Expenditure Statistical Analysis, (ongoing)

13 While the indigenous population will be overrepresented in claiming age-related benefits (i.e., State Pension), the immigrant population will claim tax credits; income-related benefits, child benefits and mobility benefits at far greater rates than the native population that has paid for them. It is non-EEA immigration that places the largest strain on the state.

14 Department for Education, Schools, Pupils and their Characteristics 2024/25, (2025).

15 In Bradford, the Pakistani community has a birth defect rate that is double the national average due to consanguineous marriages. This leads to reduced probabilities of reaching good stages of development; an increased likelihood of developing speech and language difficulties; and more absences from school due to primary care appointments, etc. (see https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c241pn09qqjo)

16 Department for Education, 21.4% of pupils possess English as a second language, (ongoing)

17 Putnam, R., E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-First Century, (2007).

18 Home Office/Department for Justice, Arrests by Ethnicity, (2024)

19 Home Office/Department for Justice, Average Length of Custodial Sentences, (2023)

20 Lammy, D., The Lammy Review: An independent review into the treatment of, and outcomes for, Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Individuals in the Criminal Justice System, (2017)

21 Sturge, G., UK Prison Population Statistics, (2024)

22 We have included this for completeness. However, it is not possible to robustly estimate the proportion of the national debt (and therefore, of the interest on said debt) to any particular sub-population.

Annexe B: The Effect of Immigration on Housing

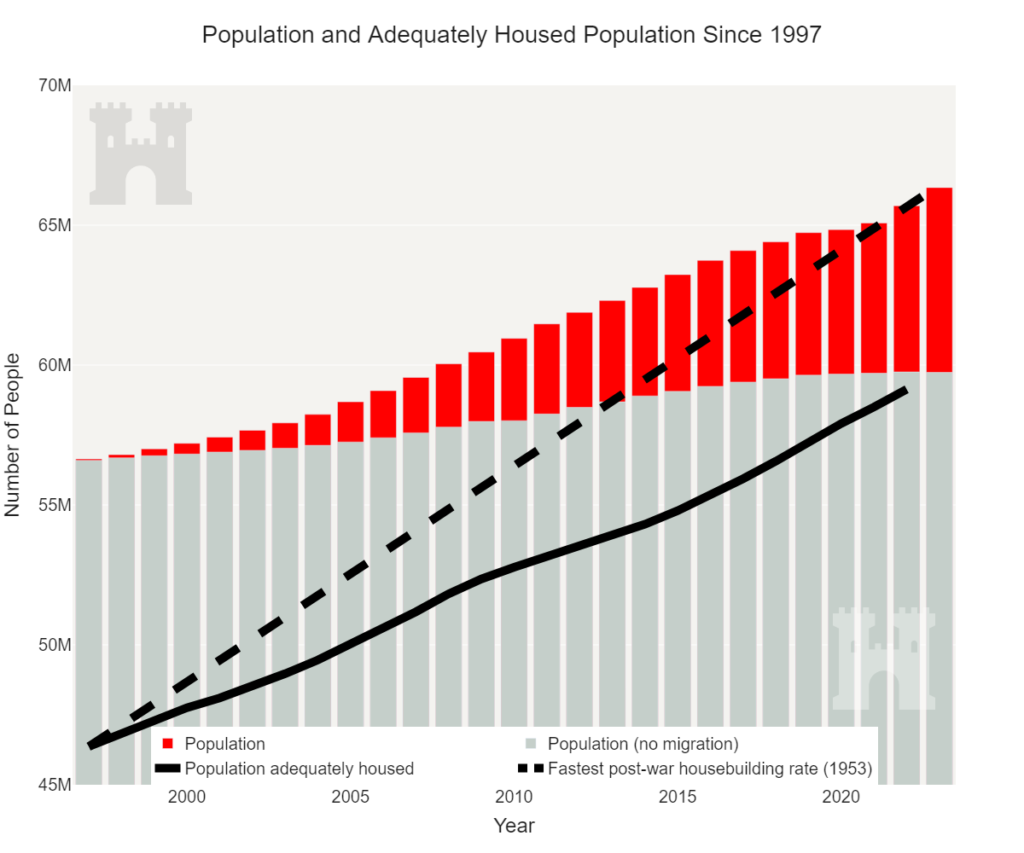

For the period 1961 to 1991, the population increased by 3.4 million people (or 6.4%). The UK built just over 9 million new-build dwellings in response which kept housing costs affordable relative to incomes.

In the period 1991 to 2021, by contrast, the population increased by 10 million people (19.1%). The corresponding increase in housing unit completions was 5.5 million dwellings. As a result, immigration has contributed to rising rents, densification (smaller dwellings) and lower day-to-day quality of life1.

In 2023, one estimate put the housing supply shortfall at 8 million dwellings2. The net growth in dwellings has kept pace with natural population growth since 1997; however, immigration means that there are not enough houses.

To illustrate this point, consider London and England. Foreign residents occupy 25% of social housing across England and 48% of housing in London (often within the desirable Zones 1, 2 and 3). This leads to the de facto subsidy of £7.5-8.0 billion in foregone rental income3 that does not show in official statistics (only housing benefits covering below market rents would be captured). However, it also has a ripple effect: those further down the waiting list are forced to seek housing in the private market, and to choose housing that is more cramped and further away from their workplace, thus pushing up rents in less fashionable areas, and so on.

As a result, private rents have increased from around 33% of income (1997) to 48% (2021) in London, and from 20% of income (1997) to 38% of income (2021) in England. This means that Real UK house prices are significantly more volatile than the most volatile parts of the United States4, and that housing affordability has collapsed5.

This is an under-reported cause of the “productivity puzzle”, and as noted by other economists, the housing crisis drives increased carbon emissions, falling fertility rates, higher inequality, greater obesity, and low productivity growth6.

1 Barker, K.,Review of Housing Supply: Final Report, (2004); see also Barker, K.,Review of Land Use Planning (2006)

2 House of Lords, 1st Report of Session, Built Environment Committee, (2021-22)

3 Ashworth-Hayes, S., The British Dream is now full benefits, a council flat and a state-funded car, The Telegraph (2025)

4 Hilber, C., and Vermeulen, W., The Impact of Supply Constraints on House Prices in England, Economic Journal 126 (591), pp. 358-405

5 Office for National Statistics, Housing Affordability in England and Wales: 2024, (2025)

6 Myers, Bowman and Southwood, The Housing Theory of Everything, Works in Progress Issue 05 (2021).